Families of Forsyth County

Atlanta History Center is uncovering and sharing the histories of the descendants of Forsyth County’s Black residents who were expelled in 1912.

As part of an initiative to continue research and bring awareness to the events of 1912, we aim to provide resources for descendants to explore and tell their family histories as conversations continue in Forsyth County and across the country on how to reconcile with the past.

The podcast 1912: The Forsyth County Expulsion and Its Aftermath tells the stories of four Black families from Forsyth County and the lasting impact of racial terror on generations of descendants.

The Brown Family

Listen to Fred Douglas Brown’s firsthand account:

Transcript:

Interviewer: This tape was made on February 2nd 19 (inaudible)…

Fred Brown: … borned in ‘92, 26th day of January.

Interviewer: And what’s your name?

Fred Brown: Fred Douglas Brown.

Interviewer: Now where did you live in Georgia?

Fred Brown: I lived Forsyth County. Cumming, Georgia.

Interviewer: Now, was Forsyth County one of the counties where they were pretty tough on Negroes?

Fred Brown: They had a, whatchacallit, they had trouble and all the Negroes had to leave there. And run them all off. Run me off with them.

Interviewer: How old were you then?

Fred Brown: I was twenty years old.

Interviewer: And what was the trouble?

Fred Brown: They claimed two Negroes, three Negroes raped a white woman

Interviewer: So they just made all the Negroes leave?

Fred Brown: They made every one of them leave. Made every one of them leave.

Interviewer: You mean just took their property and everything?

Fred Brown: Yeah. Burned, burned houses. Burned churches. Done a little of everything (it was legal enough (?)) to do

Interviewer: And the Negroes didn’t fight back?

Fred Brown: No, they didn’t fight back. They couldn’t fight back. Few of them had shotguns, but when they thought they gonna have a fight back there, they brought state guards up there and you couldn’t do nothing.

Interviewer: The state, state guards helped make the Negroes leave?

Fred Brown: No, they didn’t help make them leave, but they, they wouldn’t let a Negro stick his head out the door to fight back if he wanted to.

Interviewer: Did they tell the Negroes to leave or did the Negroes just leave because they were afraid?

Fred Brown: They went and put notices up to the houses and give them so long to move, and if they didn’t move, they’d come down and burn your house up. If you was in your own house, or do something, do anything to you, they could do.

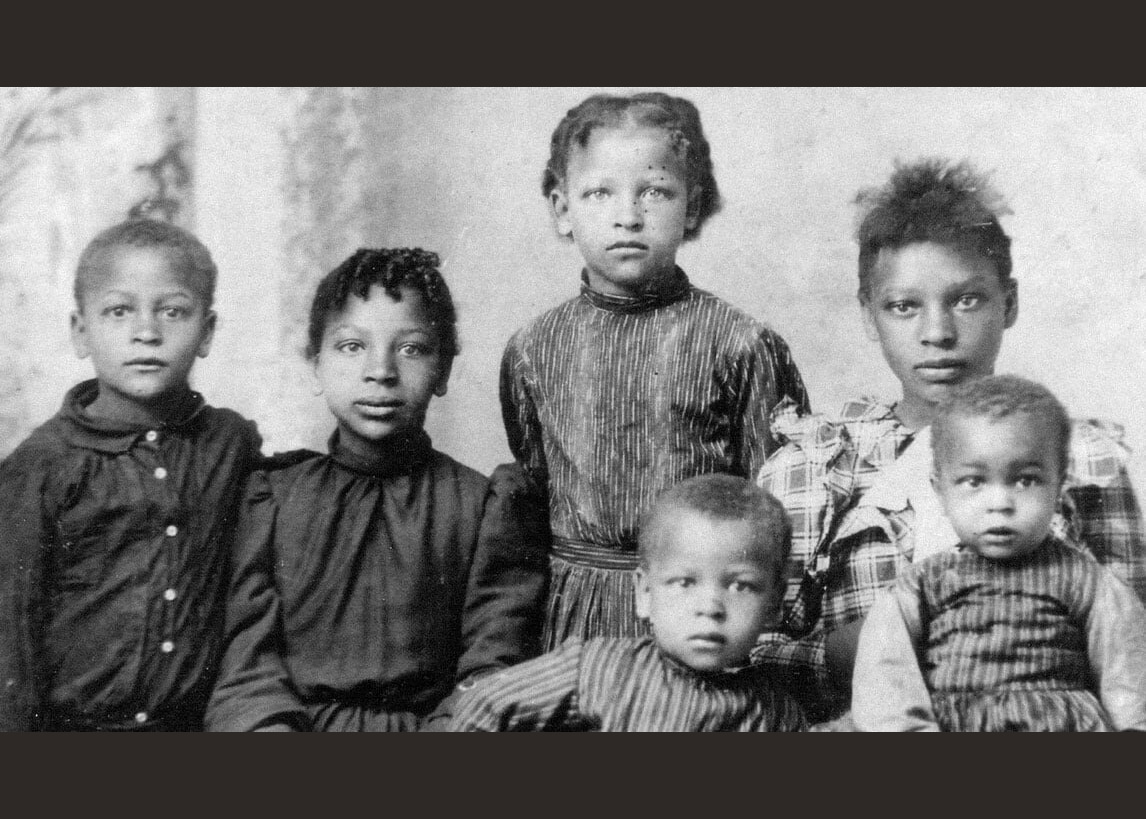

Brown Family children when they were still living in Forsyth County. From left to right, Harrison Brown, Rosa Lee Brown, Bertha Brown, Fred Brown, Naomi Brown, Minor Brown, circa 1892. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

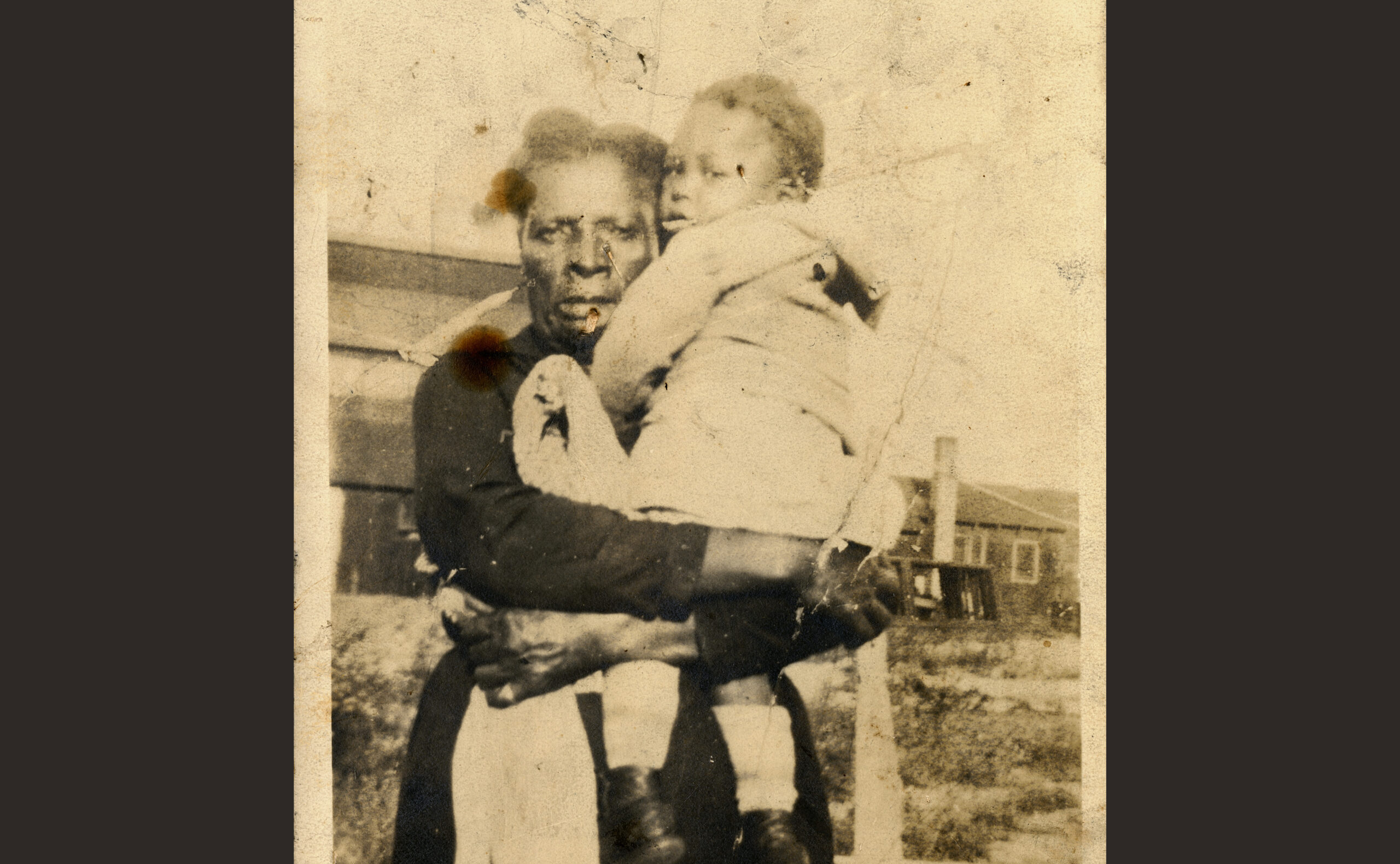

Nancy Brown, mother of Fred Brown and siblings, and an unknown child, n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

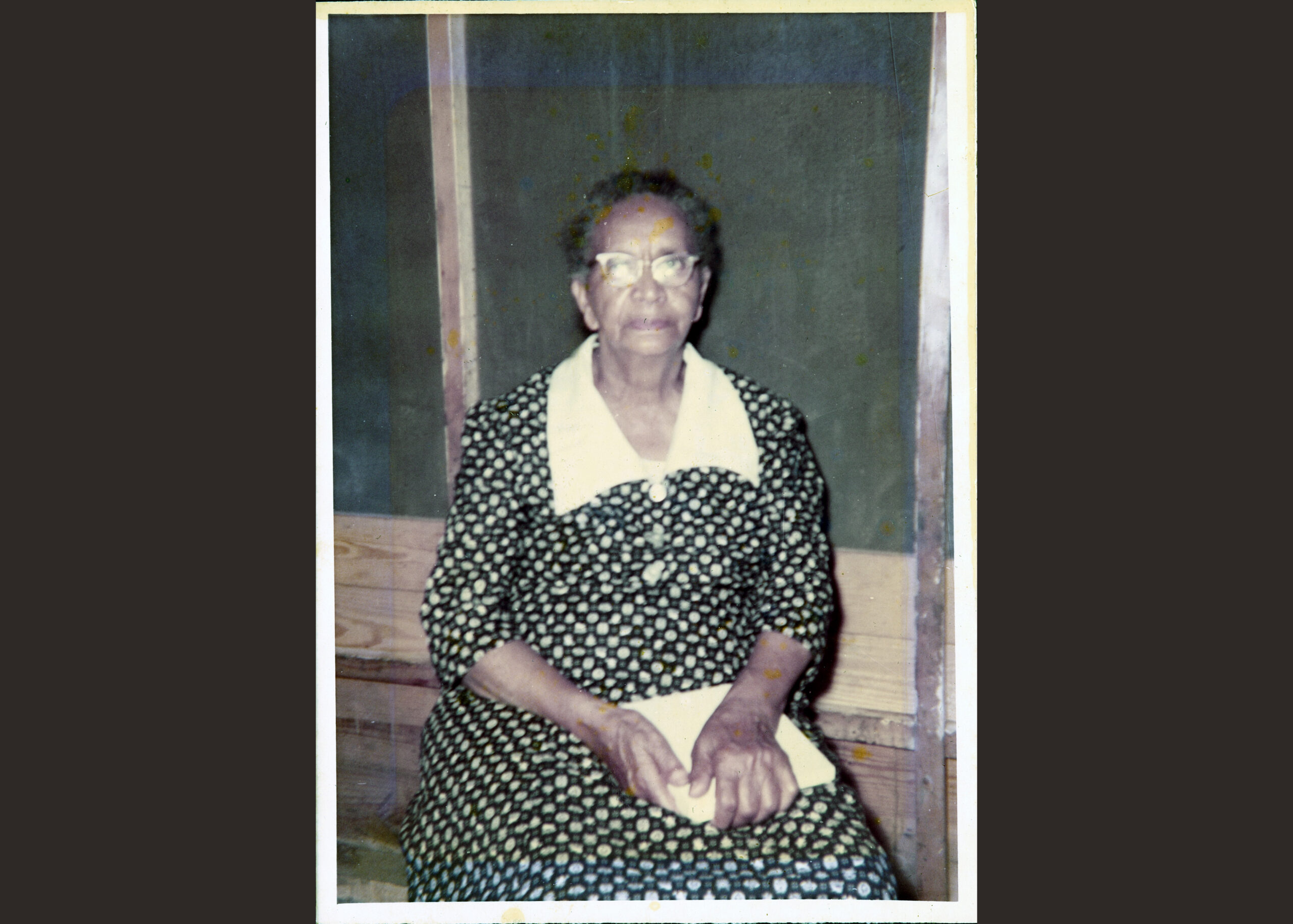

Rosalee Brown Strickland, older sister of Fred Brown, n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

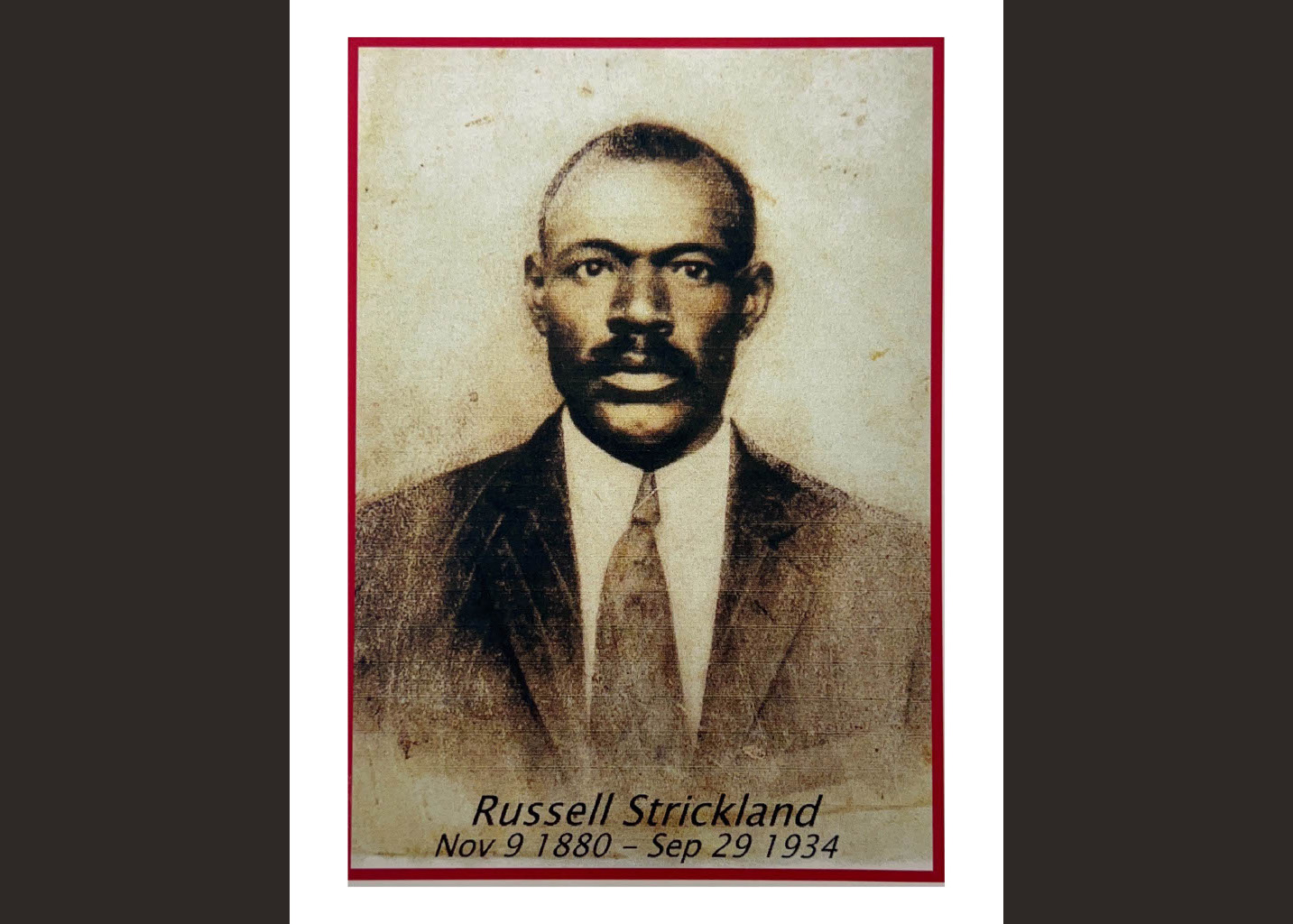

Russell Strickland, husband of Rosalee Brown Strickland. Russell was killed in 1933 by a white man, Dewey Roper. Roper was never convicted of murder. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

Fred Brown and his sons, n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

Beulah Brown, wife of Fred Brown, and their daughters, n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

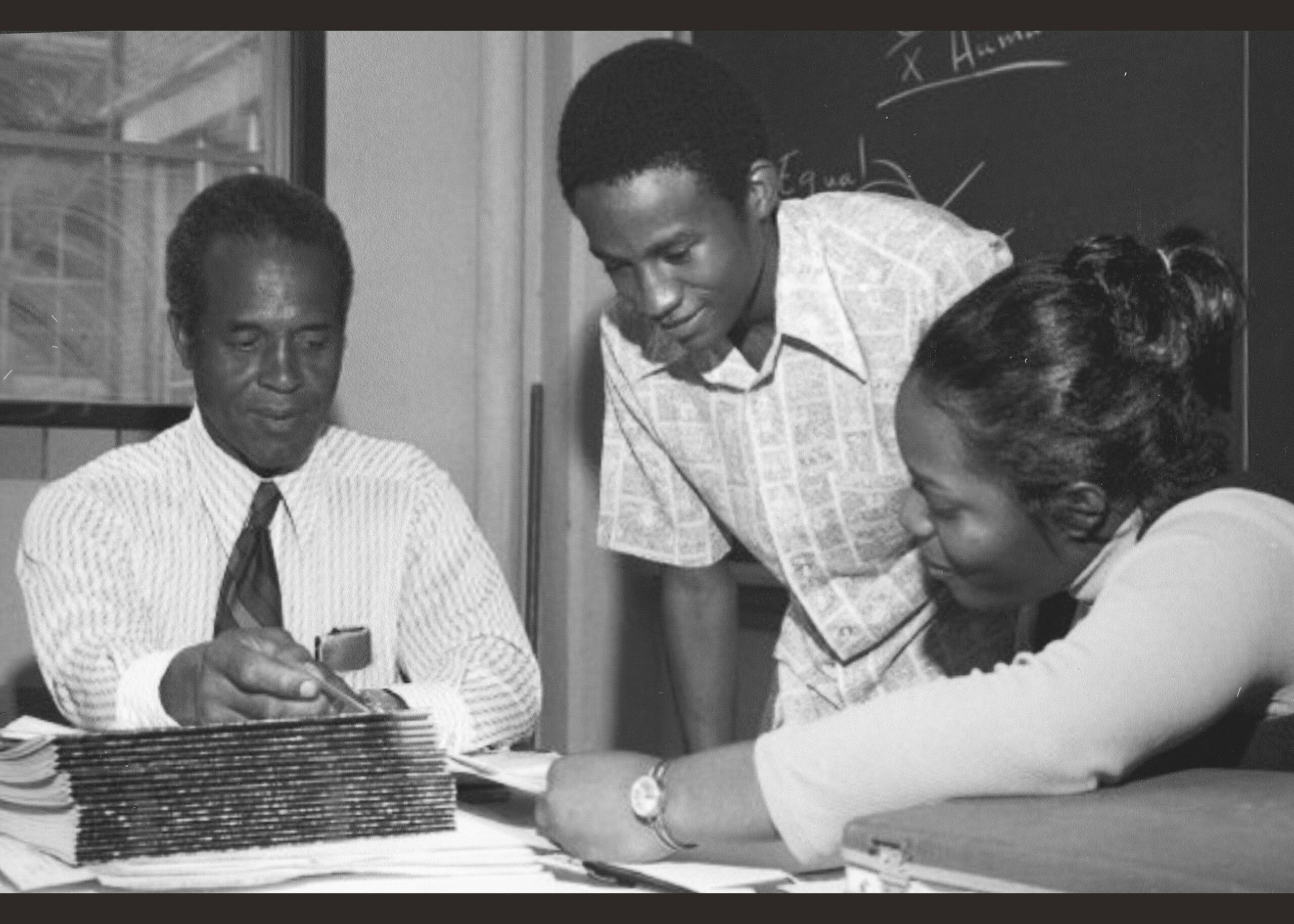

Fred Brown Jr, speaking with students at University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK). He was the first African American to have a building named after him at UTK n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

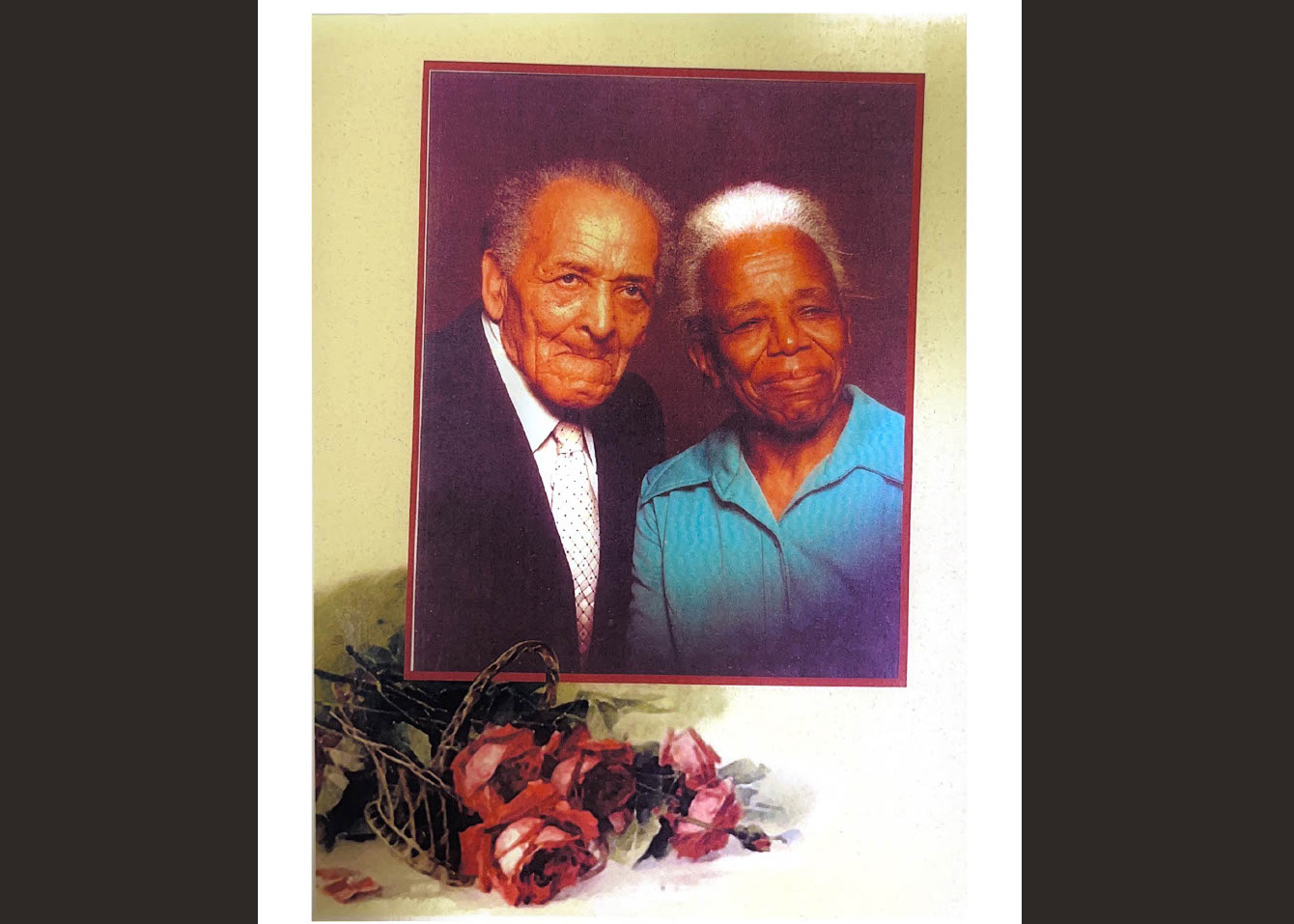

Fred and Beulah Brown, n.d. Courtesy of Charles Leroy Grogan

Charles Leroy Grogan, first row on the far left. Grogan works to research and preserve his Strickland and Brown family history, n.d. Courtesy of Annie Ruth Manning

Brown Family Profile

Fred Brown, along with his sister Rosalee and her husband, Russell Strickland, lived in Forsyth County, Georgia, at the turn of the 20th century.

The harrowing events of 1912 remain largely undocumented for the Brown family, but the aftermath profoundly affected their lives. Russell Strickland’s story took a tragic turn in 1933 when he was murdered by a white friend, Dewey Roper, reportedly over a debt involving cattle. Family accounts suggest that Russell, struggling with alcoholism, was shot and returned home, unnoticed until the next morning when he was taken to Grady Hospital, where he died from his wounds.

Russell’s brother-in-law, Fred Brown, sought a fresh start after the expulsion, marrying Beulah in Georgia before moving to Knoxville, Tennessee, for industrial work. They built a large family, having twelve children. Fred Brown’s experiences and memories of Forsyth were preserved by his son, Fred D. Brown, Jr., who recorded his father’s account in the early 1980s. This recording remains one of the only first-person narratives from a survivor of the 1912 expulsion, providing invaluable insight into that dark chapter of history.