Atlanta in 50 Objects

A pink pig and a renegade cow. A movie prop and a Coke bottle. A Pulitzer Prize–winning book and a Nobel Prize–winning icon.

How do you tell the story of Atlanta in 50 objects? We decided the best experts were Atlantans themselves—residents who cheer the Braves and rue I–285 rush-hour traffic, who understand how Civil War losses and Civil Rights victories together helped forge the city’s unique identity. Atlanta History Center asked the public to submit what objects they think best represent their town. The parameters were broad: an object could also be a person, a place, an institution, or an idea. After receiving hundreds of submissions, History Center staff assembled a collection of fifty pieces that represent the themes identified by the public. In addition to items from our own collections, we have partnered with many local institutions and individuals to gather artifacts from around the city to tell this community–driven story.

Jim Crow

As Atlanta moved into the twentieth century, it was two separate cities, one white and one black, reflecting inherent inequality. Separate was not equal, as expressed in the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessey v. Ferguson.

White and black residents lived in different neighborhoods, attended separate schools, churches, and parks, and occupied strictly segregated spaces in public areas.

Black neighborhoods received fewer municipal services with many roads unpaved, water and sewer inadequate, social programs almost nonexistent, and schools overcrowded and underfunded. In 1940, African Americans represented 30% of Atlanta’s electorate, yet less than 5% were registered to vote. The registration of African American voters proved an important key for change. By July 1946, a successful campaign increased the number of registered black voters in Atlanta to 21,000.

In 1948, Mayor William B. Hartsfield hired eight African American police officers and later supported a court ruling to desegregate Atlanta’s golf courses. In 1961, he oversaw the peaceful desegregation of Atlanta’s public schools. Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African American leaders rose to political power. As a result, decades of oppression known as Jim Crow began to give way to a more equitable society.

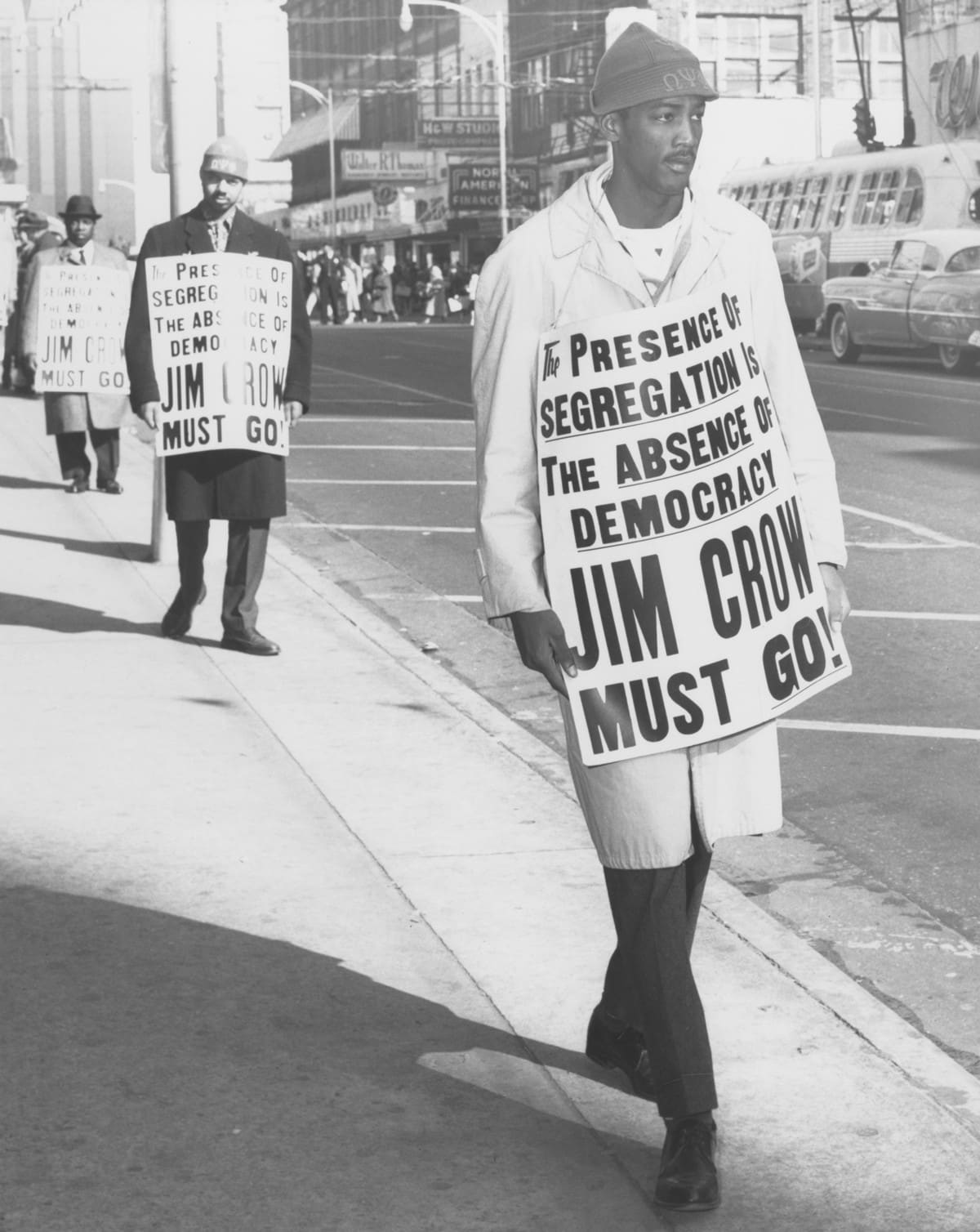

Protest against segregated facilities outside of Rich’s store in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, ca. 1960. Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, William Stanford Sr. Photographs

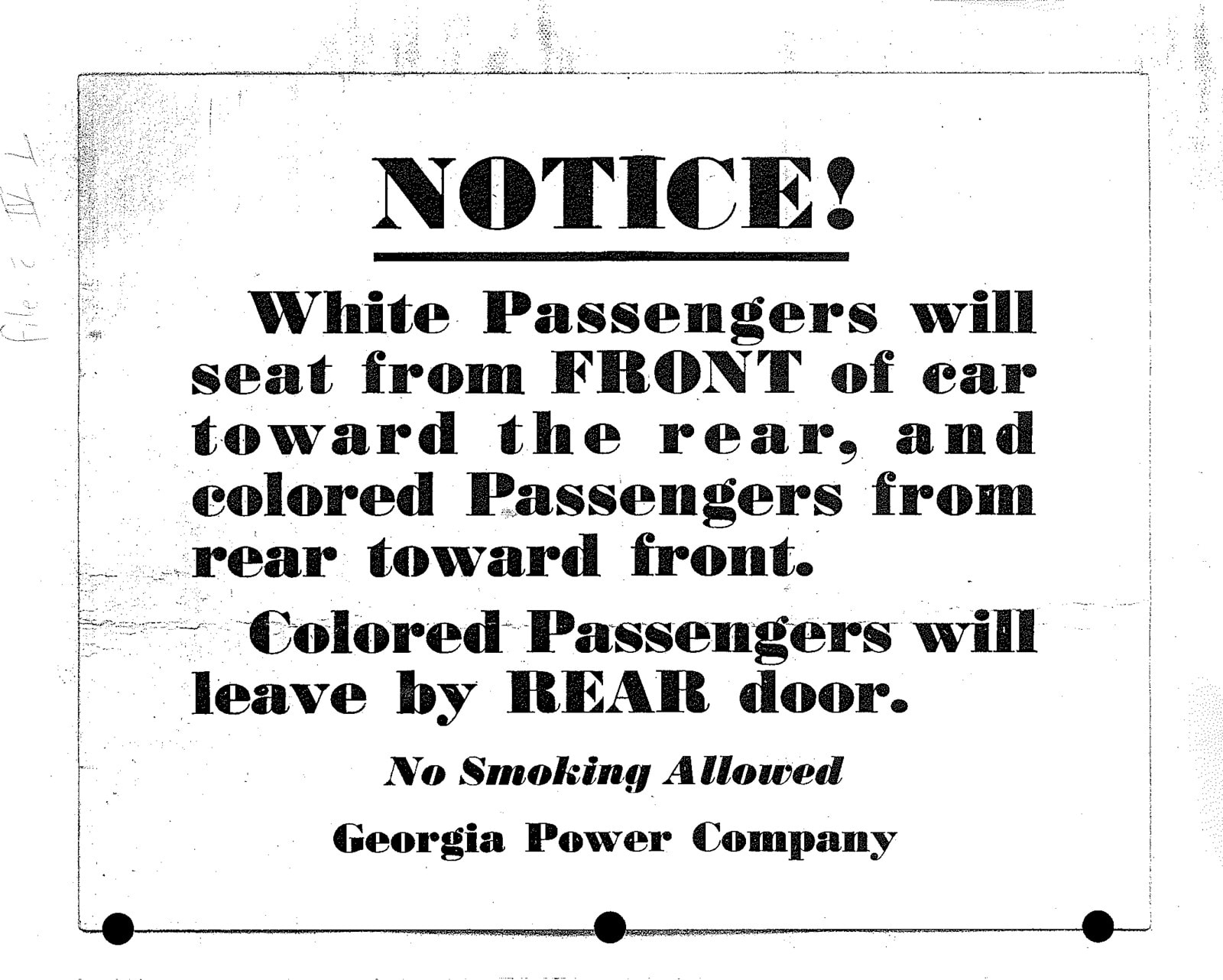

Signage from an Atlanta streetcar operated by Georgia Power Company, ca. 1945. Atlanta History Center